Have you ever found yourself in test automation projects burdened with repetitive assertions on elements, constantly needing to validate their styling or behavior upon every render? With Cypress, setting up a custom command to turn a few repetitive lines into one simple command is easy. For example, on the React TodoMVC, all uncompleted Todo items can be assumed to have a standard set of CSS styling. If we decided that we needed to check the styling of every Todo item in our automated test suite, we’d have to write out the full assertion (like below) each time we wanted to assert that the CSS styling of an uncompleted Todo was correct.

cy.get('[data-testid="todo-item-label"]')

.each(($el) => {

cy.wrap($el)

.should('have.css', 'padding', '15px 15px 15px 60px')

.and('have.css', 'text-decoration', 'none solid rgb(72, 72, 72)');

// Abbreviated assertion, but not unreasonable to have more `.and()` lines

});Additionally, if our styling ever changed (say, we wanted to change the text-decoration color to rgb(25, 179, 159)or no longer wanted to check the padding), we would have to update each place we used those assertions.

To save some headaches, we can instead create a Cypress custom command to handle our assertions. This reduces the amount of code written per assertion as well as the number of lines of code to change if the assertions need updating. Here is an example of using a custom command in Cypress.

// Custom Command

Cypress.Commands.add('shouldBeATodoItem', { prevSubject: true }, (subject) => {

cy.wrap(subject)

.should('have.css', 'padding', '15px 15px 15px 60px')

.and('have.css', 'text-decoration', 'none solid rgb(72, 72, 72)');

});

// Using the Custom Command

cy.get('[data-testid="todo-item-label"]')

.each(($el) => {

cy.wrap($el)

.shouldBeATodoItem();

});

This custom command makes the assertion much more compact, but the above command (cy.shouldBeATodoItem()) doesn’t look very Cypress assertion-y to me. Cypress leverages Chai for most of the assertions built into Cypress, and I think I’d prefer to utilize that same format for my custom assertions. Luckily, Chai and Cypress make it fairly easy to create custom Chai language chainers and integrate them with cy.should().

In our support file(s) (cypress/support/{e2e|component}.{js|jsx|ts|tsx}), we can reference the chai global (since Cypress comes with chai). Doing so will allow us to create our language chainers and have chai (and Cypress) automatically pick up our custom language chainers.

chai.use((_chai, utils) => {

// Custom Chainer code here!

});I’ve found that the easiest way to create a Custom Chai Language Chainer is to use the .addProperty method.

chai.use((_chai, utils) => {

utils.addProperty(_chai.Assertion.prototype, 'todoItem', function() {

this.assert(

this._obj.css('padding') === '15px 15px 15px 60px' &&

this._obj.css('text-decoration') === 'none solid rgb(72, 72, 72)',

'expected #{this} to be a Todo Item'

)

})

});Breaking the above down:

- utils.addProperty()

- Used to add a property to the Chai namespace

- _chai.Assertion.prototype

- Used to specify that the property is to be on the chai.Assertion namespace

- todoItem

- Name of the language chainer

- function()

- Important to use a function declaration and not an arrow function since our code uses scoped this

- this.assert()

- Chai assertion function, using the two-parameter signature, where the first parameter is the assertion (Boolean), the second parameter is the failure message if the positive assertion fails (to.be)

- this._obj.css()

- this._obj is the subject of the assertion. In our cases, this will be a JQuery object yielded from Cypress, so we can use JQuery’s .css() function to find CSS values.

- #{this}

- The #{} syntax is used to pass in variables to Chai. This is what gets that nice printout in Cypress, where it says expected <label> to be visible

In our test, instead of our custom command, we can use our custom Chai language chainer!

// Custom Command

cy.get('[data-testid="todo-item-label"]')

.each(($el) => {

cy.wrap($el)

.shouldBeATodoItem();

});

// Custom Chain chainer

cy.get('[data-testid="todo-item-label"]')

.each(($el) => {

cy.wrap($el)

.should('be.a.todoItem');

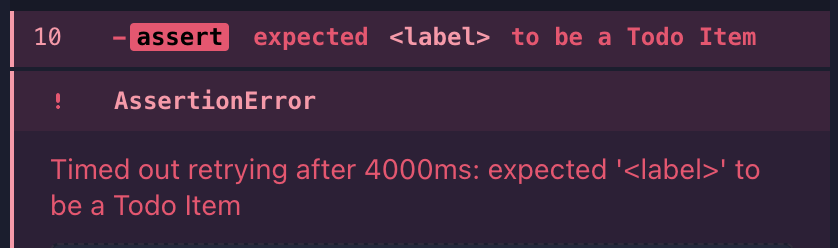

});Unfortunately, tests don’t always pass. It’s easiest to troubleshoot failing tests when the errors from the failing tests are specific to the issue, and our current implementation of the language chainer does not give us a clear picture of why our test would fail.

If an element doesn’t meet our assertion for a Todo Item, we don’t know why the element isn’t meeting that assertion. To get that data, the simplest way is to make a series of soft assertions. The object yielded to this._obj is static (at least per-iteration through the assertion) and can be used synchronously, so we can store our soft assertions as booleans.

// Adding Soft Assertions

utils.addProperty(_chai.Assertion.prototype, 'todoItem', function() {

const isPaddingCorrect = this._obj.css('padding') === '15px 15px 15px 60px'

const isTextDecorationCorrect = this._obj.css('text-decoration') === 'none solid rgb(72, 72, 72)'

this.assert(

isPaddingCorrect && isTextDecorationCorrect,

'expected #{this} to be a Todo Item'

);

});But that hasn’t changed our error messages yet, to do that we’ll need to change the string in the second parameter. We can manually construct our error message by checking if the soft assertion is false and, if so, adding the failure to our custom error message.

utils.addProperty(_chai.Assertion.prototype, 'todoItem', function() {

const isPaddingCorrect = this._obj.css('padding') === '15px 15px 15px 61px'

const isTextDecorationCorrect = this._obj.css('text-decoration') === 'none solid rgb(72, 72, 72)'

let errorString = 'expected #{this} to be a Todo Item'

if (!isPaddingCorrect) { errorString += `\n\t expected padding to be 15px 15px 15px 61px, but found ${this._obj.css('padding')}` }

if (!isTextDecorationCorrection) { errorString += `\n\t expected text-decoration to be 'none solid rgb(72, 72, 72)', but found ${this._obj.css('text-decoration')}` }

this.assert(

isPaddingCorrect && isTextDecorationCorrect,

errorString

);

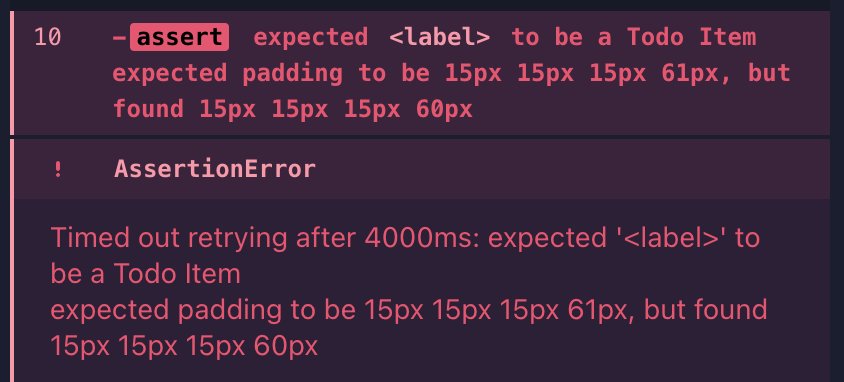

});In this example, we’ve changed the expected padding value to be 15px 15px 15px 61px, and we can see the error message displayed:

The changes accomplish our goal of being able to use a custom Chai language chainer and have an informative error message on what failed the assertion. But we’re doing repetitive tasks (iterating through some boolean values) and hardcoded values twice. We can improve our code by reusing the common values to run our soft assertions and write error messages.

// Step 1: Create an expected data object

const expected = {

padding: '15px 15px 15px 60px',

'text-decoration': 'none solid rgb(72, 72, 72)'

};

// Step 2: Create a combined Soft Assertion value, using Array.every()

const hasCorrectProperties = Object.entries(expected).every(([key, value]) => this._obj.css(key) === value)

// Step 3: Use array.map() to generate our error string

this.assert(

hasCorrectProperties,

"expected #{this} to be a Todo Item" + Object.entries(expected).map(([key, value]) => { if (this._obj.css(key) !== value) { return `\nexpected #{this} to have ${key}: \n\t${value}, \nbut found:\n\t${this._obj.css(key)}`} else { return '' }}).join(''),

"expected #{this} to not be a Todo Item"

);Breaking the above down:

- Object.entries() returns an array whose elements are arrays corresponding to the enumerable string-keyed property key-value pairs found directly upon the object

- In simpler terms, it returns the key-value pair as the first and second position in an array, like [key, value]

- The every() method of Array instances tests whether all elements in the array pass the test implemented by the provided function.

- We can take an array and pass a “test” function into the callback and eventually receive a boolean value if all “tests” pass.

- Object.map() will return a new array with the transformed values, in this case, our error strings, which we then join using array.join().

The important thing to remember is that the key values for the expected data object must match the CSS properties, as we use that key value to search for the CSS property. (If we were to use the more JavaScript-like textDecoration instead of ’text-decoration’, this would not work.)

A definite improvement! But if we wanted to create several language chainers easily, we’d need to copy over the same few lines of code each time. We can abstract this to a few helper functions and simplify our setup within the utils.addProperty().

/**

* @param {JQuery<HTMLElement>} ctx -> context, the element passed into the assertion

* @param {object} expected -> expected data object; key is the css property, value is the expected value

* @param {string} elementName -> name of the element being tested

* @returns boolean, string

*/

const assertChainer = (ctx, expected, elementName) => {

const hasCorrectProperties = Object.entries(expected).every(([key, value]) => ctx.css(key) === value);

let positiveErrorString = `expected #{this} to be a ${elementName}\n`;

Object.entries(expected).forEach(([key, value]) => {

if (ctx.css(key) !== value) {

positiveErrorString += `\nexpected #{this} to have ${key}: \n\t${value}, \nbut found:\n\t${ctx.css(key)}\n`;

}

});

return [hasCorrectProperties, positiveErrorString];

}

// Use

chai.use((_chai, utils) => {

utils.addProperty(_chai.Assertion.prototype, 'todoItem', function() {

const expected = {

padding: '15px 15px 15px 60px',

'text-decoration': 'none solid rgb(72, 72, 72)'

}

this.assert(

...assertChainer(this._obj, expected, 'Todo Item')

);

})

utils.addProperty(_chai.Assertion.prototype, 'completedTodoItem', function() {

const expected = {

padding: '15px 15px 15px 60px',

'text-decoration': 'line-through solid rgb(148, 148, 148)',

}

this.assert(

...assertChainer(this._obj, expected, 'Completed Todo Item')

);

});

})(Curious about those three dots preceding assertChainer above? It uses the spread operator to turn assertChainer’s returned array into separate variables.)

Caveat:

I did not use the third parameter in these examples when constructing the custom Chai language chainers. This prevents the language chainer from accepting a negative assertion. When attempting to assert via should(‘not.be.a.todoItem’), the following assertion error is thrown, and the assertion is not attempted.

If you would like to add support for a negative error message, simply provide the error message as the third parameter in your assert() function.